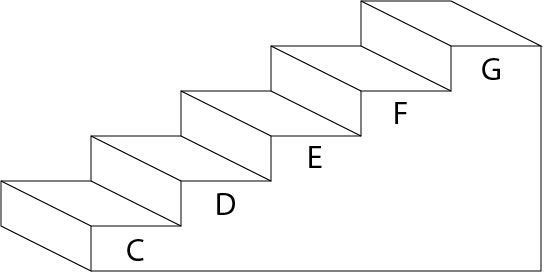

An understanding of music theory, and of composition, starts with an understanding of scales. A scale is a series of closely spaced notes in order from low to high, or high to low. Scale means “staircase”.

In Western music, the most common scale is the C Major Scale. The major scale is also called the Diatonic (seven note) scale. The major scale can be thought of as the ruler by which everything else is measured. By understanding the structure of the major scale, we can easily understand how all other scales and chords are named.

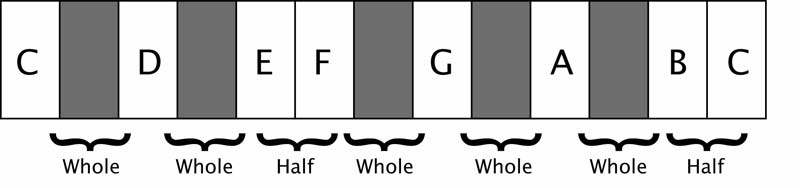

When we move from one note to the next in a scale, it is called a step. As we mentioned before, the major scale can be thought of as a ruler. Unlike an ordinary ruler, however, the elements of a major scale are not evenly spaced. There are two sizes of steps called a half step and a whole step. A half step is the smallest unit in our musical system. It is the distance from one note to the nearest neighboring note. On the piano it is usually the distance from a white key to the nearest adjacent black key. On the guitar, it is the distance from one fret to the neighboring fret. A whole step, on the other hand, is twice as large and is equal to two half steps.

The C major scale is created by starting on C and following the pattern whole whole half, whole whole whole half. Notice that most of the notes are separated by a whole step, except between E/F, and B/C where you find half steps.

This pattern is so fundamental to Western music that it is literally built in to the structure of the piano and many other instruments. If at any time you forget the pattern of half steps and whole steps, simply look at the piano keyboard. The places where you don’t see a black key are where the half steps are located.

What gives any group of notes its particular sound, as well as its name, is not the notes themselves, but how those notes are spaced. Similarly what makes a major scale major is not the notes it contains, but the spacing of those notes. As long as the notes follow the pattern whole whole half, whole whole whole half, the notes will form a major scale. If we replace the letters with numbers in the picture above we get a more general representation of a major scale:

Now we can see that the half steps are between 3/4 and 7/8. Each number is called a scale degree. This simply indicates what number note it is in the scale. The distance between any two scale degrees is called an interval. If the major scale can be thought of as a musical ruler, then intervals can be thought of as musical inches. The term interval will be used again and again throughout this book.

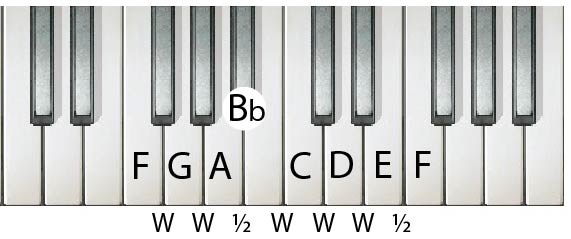

There are twelve uniquely different notes in our musical system. As mentioned before, it is the spacing between notes that is important. In the first scale, we used C as our starting point. If we start on a different note but use the same spacing, we will get a different scale. For example, to create an F major scale, we start on the note F and go whole whole half, whole whole whole half:

Look at the interval from A to Bb. We know that in order to keep the pattern of whole whole half, whole whole whole half we require a half step here. However, in its natural state the interval from A to B is a whole step. By choosing Bb instead of B, we force the interval to become a Half Step.

Now let’s look at another example. We will form a major scale by starting on G and following the pattern of whole whole half, whole whole whole half.

Look at the interval from E to F#. We know that in order to keep the pattern of whole, whole, half, whole, whole, whole, half we require a whole step here. However, normally the interval from E to F is only a half step. Therefore we replace F with F#, forcing the interval to become a whole step.

In the workbook, please fill out the worksheet entitled Notes in Every Key.